27th November 2021

Slide 1

Slide 2

Slide 3

Slide 4

Slide 5

Slide 6

Stepping up Becoming a leader in your team

Welcome to Stepping up – Becoming a leader in your team Hello folks! I hope you’ve been enjoying all the great sessions today. As you can tell by my accent, I’m one of the several global speakers joining you today. I hail from the town of Ottawa, in Canada. Make sure to join the Discord to ask questions or chat, and I’ll jump in there after to see how I can help! Today, I want to chat with you about that awkward moment when you go from being just another one of the team, to then leading that team.

When you first transition to go from member of the team to leading that same team, usually it is because you demonstrated some sort of expertise. Some sort of “leadership quality“, maybe. Others see it. Maybe you are really opinionated. Maybe you are really passionate about something you believe in. Maybe you’ve shown you can really work up and down the ladder and across departments. Whatever it is, people see that you have “it“. Now they want you to take this on.

Then your teammates start calling you “boss”.

But while you’re doing this, you’re finding it hard, to try to give away being the hero, building the thing, saving the day, being that expert. There’s a dopamine hit you get every time you push a task to done. And taking on strategic work, it could take months, it could take quarters, it could take years before you see success from your efforts. So it can be hard to let that go of that other side of the world.

My name is Jason St-Cyr, I lead the team of Developer Advocates over at Sitecore. I want to talk to you about the times where I’ve had to go through this transition myself, and hopefully how you can learn from it.

Slide 7

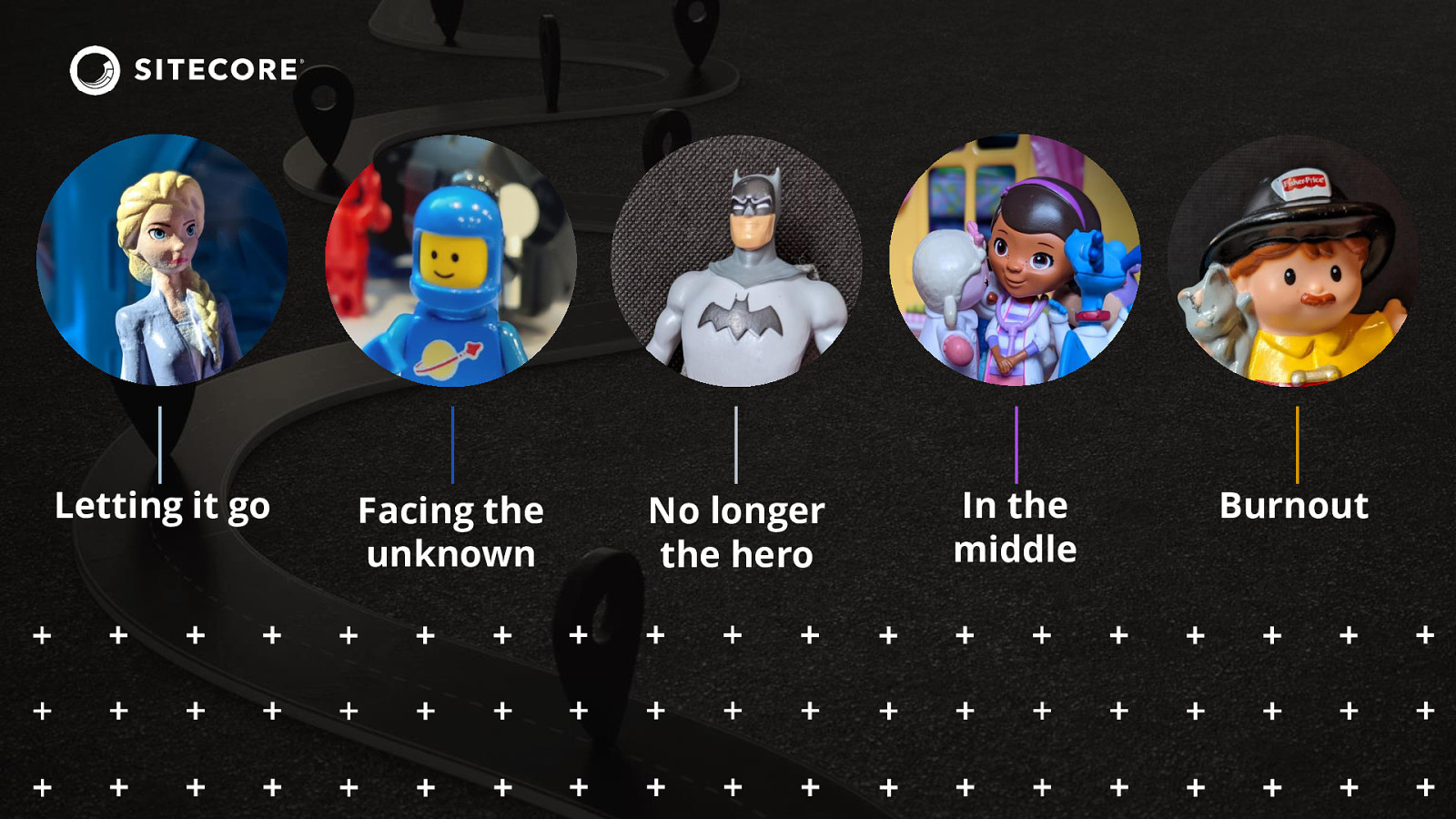

I want to take a look at a few challenges over the course of this session:

First, how do we learn to delegate, and kind of balance our independent and manager roles?

Secondly, how do we go about doing a different style of decision making. You know, when you’re not sure how things are really going to turn out?

Next, why don’t we take a look at how we switch your mindset away from not being the subject matter expert anymore, not being the hero, and instead being the coach?

We also want to take a look at that “in the middle” part of middle management

And finally wrap up with a little bit about mental health and trying to prevent burnout

Slide 8

You might have noticed a little bit of a theme around toys. This talk is a lot about stories, and what we learn from them. Now as a dad, I’m finding that stories are a great way to use toys and teach my kids about something and have it resonate.

Stories allow for us to create an emotional connection. It also allows us to have an easy recall for something. So, for example, if you’re into Star Wars, I might say something like “Let the Wookie win” and you’d know exactly what point in that story I’m referring to and you’d be transported back to it.

So, we’re going to go through a lot of stories today, and hopefully you are going to be able to use those stories to come back to a learning moment. And for those of you out there creating your own stories right now, make sure that as you’re learning, you are creating those recall moments that you can come back to.

Now let’s get started!

Slide 9

Letting it go.

Now the first challenge I wanted to talk about is delegation. When I speak with my colleagues and other managers, a lot of us have had the same experience. In general, it seems to be very hard when you’re inside of a team, and transition to leading it, to give up some of those tasks that you used to be doing. This was definitely true for me.

Slide 10

To delegate, or not to delegate

The first management role I took over, I was in a small product company, leading the R&D group. Smart team, really great people. I found I was doing a lot of development work, even tough I was supposed to be managing the team.

Now I look back at it, and, I guess what happened is, I gave myself a choice. I said to myself:

Hey, you could throw away almost a decade of experience and everything you’re good at and really focus in on this management job

Or, you could do two jobs really poorly,

Or, you could do both jobs and focus on them.

So of course I went with that option, right? I learned so much: I learned about SWOT analysis, I learned about product management, release management, and how to burn out in under a year.

It was super tough to give up those tasks that I was used to doing. I knew I could do them, I knew it would take time for me to get somebody else to do it. Not only that, everybody’s plate is super full, so if I’m giving this to somebody else, something’s going to drop.

How do I need to handle this?

Eventually, I burnt out, I left that job, somebody had to pick up those tasks anyway, except now I wasn’t there to help or guide them through it. And you know what? They did great. I was the only one preventing that team from going forward. That was a big learning moment for me.

Slide 11

Am I holding the reins, or pulling the sleigh?

Now I’ve had this repeat a few times, where I’ve done this transition into leading the team, and, like I said, it was hard to let it go. I knew I needed to delegate, I knew I had tasks I shouldn’t be doing. Even just last week I started training somebody up on how to upload videos into our portal. This is probably something I probably shouldn’t have been doing for years.

I needed to get better at looking at my tasks and seeing what type of things were they. Are they driving tasks, or are they more working, independent contributor task.

The first question I had to ask is: Is this kind of a strategic, driving the team type of task. That’s probably something, as a leader, I should be working on.

Is it something that requires absolutely no expertise? If literally anybody could pick this up with some basic access and basic, you know, “here’s what you should do”, that’s definitely the first thing I should get off my plate.

Now the hard one is the transferable expertise. Meaning, someone could learn it, but I’m probably the only one who knows how to do it and it takes someone to actually ramp up. Those are the tough ones to let go.

Now on the slide here, I refer to the concept of holding the reins, the sled, the driver. As a team, the sled needs to get somewhere. And someone is doing the really hard work of making sure that sled is moving. But the driver needs to be able to take a look, give nudges and guidance to make sure the sled gets to where it’s supposed to go. Together, you succeed. And you can’t do both.

Slide 12

What did I learn?

So what did I learn? Well, I learned the “Don’t do two jobs at once” thing. That didn’t work for me. I also learned something that I didn’t know then, but I see now: that I was blocking the team from growing. I was keeping them from expanding their own capabilities.

And from doing it better than I could.

Part of me delegating, apart from me getting my load lighter, was making sure the right work was going to the right people who had the right expertise.

Trying to do it all meant that stuff is not getting picked up by anybody else. I’m still the bottleneck, I’m not providing growth opportunities. The job’s not getting done right.

I had to learn to trust my team. I needed to be able to say “This is not in my ballpark, this should be somebody else’s work”. And I’m not going to say that I’ve solved this completely today, this is an ongoing challenge, but I like to think that over time we get better and better at this. Better and better at being able to give away work that somebody else could probably help us with.

Slide 13

This is NOT like building a spaceship!

Now the next challenge I want to talk about is part of becoming a leader and making decisions on things that are not always clear choices. I needed to accept that maybe I didn’t have all the answers, right? But being on the team, I’m used to being the expert about something. And also I really enjoy being right! I have been in conversations where I have argued well past the point of being constructive just so I could be right.

When I was part of the team, my opinions on a subject were only a part of what leadership was taking into account. And probably that any decisions I made are going to impact me, I’m probably going to have to fix it, I’m the only one affected. So someone would ask “Is this hill the one you really want to die on?” my answer would usually be along the lines of like “Yes I want to fight on every hill!” meaning I will go and use my opinion, and what I believe in every time.

And I found it difficult to take that kind of very self-directed decision making model out into a leadership position. Because now my decisions affected somebody else. Now I could affect company strategy. But I had a hard time accepting that maybe I was wrong about something. And looking back there’s probably a lot of times I tried to, you know, play all the odds to make sure I could always be right. But sometimes I was just being very rigid, sticking to what I knew.

Slide 14

On lacking flexibility

And on that, that being inflexible, was definitely a problem early on. Back in the day, I remember sitting in some boardroom talking about a product release with some other managers, as managers like to do, and somebody drew a cliff and was implying we were going to be going over a cliff. I don’t know why the cliff was there, what I remember was I didn’t care. I didn’t care about what the customers felt I didn’t care about what other people’s opinions were about the situation.

We had issues in the software release. My team had flagged that the release candidate was not ready. I was going to fight that we had to make sure that this release was solid, did not matter what the customers needed or what deadlines they had. Now it never occurred to me even though I was wrong. Right? I was thinking about software delivery as a software developer, a practitioner. I was looking at as someone that wanted to fight for the right to do so for delivery the way it should be done.

But I wasn’t being flexible I wasn’t willing to take input from other sides, from the business, and admit that I might be wrong or that there might be another way.

Slide 15

Meet Chad

Another side of this, trying to make decisions, accept possibly not having all the answers, is in the hiring process. A long time ago I was involved in the hiring process for new employee. Now they wouldn’t be reporting to me directly, but I was in the hiring decision, I was mentoring them, ultimately I was responsible for their success.

So several candidates later in the process, I recommended we hire Chad. Now their name was not actually Chad, but for the purpose of the session their name’s Chad.

Chad was extremely good in the interview, great communication skills, good sense of humour, really matched with the culture vibe of our team, I thought we could work together. Usually if someone can learn and has really good communication skills, you can usually upskill them on whatever they’re lacking.

Now, the first project we got together on was a massive disaster. Even our most experienced people on the team were struggling, like this was not the best intro. But Chad seemed to be struggling a little bit more. I chalked it up to maybe learning new skills, being new, not the best first project to take on.

I ignored some red flags. I only saw them later. Things like:

Chad wasn’t learning from mistakes, the same issues were popping up again and again.

And Chad didn’t seem to absorb information, you’d often have to explain the same concepts over again.

And Chad was ignoring details, trying to get things done fast rather than focusing on, you know, doing it right.

I wanted to keep investing, right? It definitely couldn’t be that I was wrong about this person, right? There must be something that I’m doing, that I have not put this person into the right position yet, for them to succeed. I must have been right, right?

But the project failures continued, project after project. Eventually we had to admit this was not working.

I was wrong.

And I can see that, now, with conviction. But at the time? It was really hard to admit that I had made a mistake in how I chose someone to join our team.

Slide 16

What did I learn?

Now what are these types of scenarios each mean. Well, I learned I needed adapt my thinking. I needed to accept that I’m not always right, I didn’t always have all of the information. I had to be flexible, I had to think, what the management buzzword handbooks always say, right, “Think of the bigger picture”.

It wasn’t that I should ignore my instincts, or ignore the expertise I had built up, but I needed to bring all of the parts of the solution together and take everything into account. Everything that was available to me was part of the final solution that would work. It didn’t all just have to come for me.

Slide 17

I work alone.

The next challenge I want to talk about is the challenge of switching off the expert mode. And going through that whole “I was the expert on the team and now I’m the boss”. A lot of times when we’re on a team, we have some kind of demonstrated excellence, we have an ability to execute, we have a certain skill set that we built time over and and we are really good at something. When you go and you switch to that leadership job for the first time the skill sets don’t necessarily always match up and you feel like you’re starting over.

You’re now expected to be really good at coaching and mentoring, and project management, and strategic thinking. But when you make that first move, it can be hard to feel comfortable. I know I felt like I had no idea I what I was doing, right? I was used to knowing what I was doing, I used to leverage experience to do what I did. I knew how to work on my stuff, I knew how to take those tasks. But things like delegation, I mean, this was all going to be new to me.

Slide 18

You expect me to trust you?

And in that sense where you start feeling like you don’t really know what’s going on, I had the struggle of how to build trust in my leadership, right? Because here I am, thinking I have no clue what I’m doing. Kind of like imposter syndrome, except I actually have no clue what I’m doing!

I found it very awkward, even if my teammates didn’t, trying to adjust a relationship with them. How are you going to think that I’m going to make the right decisions? How am I going to build you up some kind of trust that I can do this right?

Now eventually I was able to build that up, and change those relationships, but it wasn’t Management training or anything like that that they gave me the tools to do it. I eventually had to become comfortable making decisions, but doing a few things I could build up trust. The 3 things that I started keying in on were:

One: how do I get some kind of demonstrated competence, an easy win early, right? So everybody in this new model gets to have a success.

Secondly how do I improve my level of empathy and show that I’m listening and show that I’m understanding their situation.

And third, a lot of honesty. That was a really big part for me but I think empathy was probably the hardest one early on for me to adjust and learn.

Slide 19

Use your Spidey-senses

Now one other thing that I encountered when making that transition from team member into leadership, was that when you do it within the same team you have a lot of expertise in what the team is doing right now, especially early on in that transition, It’s very hard to stop providing expertise.

I was on a call with one of my reports once, and they were asking me a question and my head’s in expert mode and I go to this long-winded answer trying to show all the things that could be looked into, different options blah blah blah blah.

At one point, thankfully, they interrupted and said “Jason, I know about the options, I’ve gone and looked at, I have a plan. What I’d like to know is if this is one that you’d be able to support me in, whether you see any issues with it?”

There’s a light bulb moment for me, right? It’s like I’ve got the wrong hat on. In that instance I needed to be aware. I needed to see that this was not someone coming to me for my expertise. I needed to be less directive, less heavy direction and more of a supporting coaching model, right and listening. You know the, I needed to realize that people aren’t always going to be coming to me anymore about my expertise. Right? They’re coming to me for a different reason. I’m no longer that expert on the team. I’m not expected to be the expert on the team.

Slide 20

What did I learn?

So all of these different scenarios what they added up to was that I needed to learn how to listen. I didn’t have to be the expert, I did not need to focus on me. I needed to change the focus to my team. That meant empathy that meant being able to understand and be situationally aware of what does someone need. And I’m not saying that that is easy but it is definitely something that I am trying to focus on more, is being able to react to the situation.

Now one of the things that that expertise is really helpful for, is understanding what our team members are going through. Because we’ve done it, we’ve just been there, we know exactly what they’re working on, pretty much, so it is really easy for us to empathize and understand the kind of challenges they’re going to go through.

Day to day this is something you got to get better and better at. Definitely something that I am trying to work better and better at this, over time.

Slide 21

Caught in the middle.

Now one topic I want to touch on was the middle part of middle management. When you first take a step up, and start becoming the leader in a team, you start having these new sensations. Usually the first time that you’re going to have multiple directions that you are pushing out on, and that are pushing in, and sometimes all the directions are coming in on you. And that can be actually really pressuring and like you feel like it’s too much. Sometimes you can adjust to it, sometimes you can just adjust to how much is coming in and kinda deal with it over time. But sometimes you have to start pushing back.

Slide 22

Maybe the team needs a check-up

I can think of a time, several years ago, where I was working at an implementation agency. Probably the most extreme scenario where I felt really pushed on all angles. I did not handle it very well. I was not paying enough attention at the time to what my team was going through and what I needed to do for them.

You see my team was struggling with this project. I mentioned earlier the project that was horribly awful and that noone should start on? Yeah, that one.Everything was going wrong. If there was an estimate for a timeline, [Whoosh noise] out the window. There was no way that that was going to happen. My team needed the timeline to change. But the customer, they had a very specific real-life date that could not be moved. There was no flexibility. My management wants us to stay on budget, my team needs a change in the timeline, the customer is not willing to budge on anything. I had never felt the Iron Triangle more than in that instant.

So I sat down and came up with a plan. Something I thought could work. Several of the things that were in the real world were happening on different dates. Maybe there was a way for us to shuffle around some of the work and instead of trying to do it all up front, deliver it a little bit incrementally into their production mode. Be able to get them where they needed to be by the different times that they needed. Work with a customer, prioritize everything, let’s figure something out.

Sounded like a great plan, until it went completely wrong.

You see, to make it happen, my team wound up having to do a ridiculous amount of overtime just to barely make the deadlines.

So we we’re over budget, my management was not happy. The customer didn’t get everything they wanted when they wanted it, and we were barely making it in time for them, they weren’t happy. My team? Having to do all that overtime? They were not happy.

The whole thing goes into this massive retrospective. “What went wrong?” and there were a lot of things that went wrong. But when I look back at it, the thing I regret is that I didn’t fight to say “No”. I didn’t fight for my team. I didn’t fight to say “We shouldn’t be doing this.” I regret that.

Slide 23

Inexperience can be a hurdle

Now there’s another example of being in the middle from back of my product days. I was very new to this whole leadership thing, and meeting executives to talk about a product roadmap. I didn’t know it at the time but we were doing something that was basically Agile development. We would do weekly product releases and we were getting QA feedback on those, getting the release candidates out. And we would prioritize all of our work constantly, refining what was in our backlog, and releases would have a flexible scope.

This made us really happy because we were very predictable, we knew when our release was going to go out and development could make sure that we were adjusting the scope on the fly, all the time, worked really well.

Except that that was not what worked for upper management.

They didn’t want to know that release 4.7 was coming out. They wanted to know what was in it. And I tried to explain how the scope is flexible we didn’t really know what was going to be in it, but they needed to have some idea about what our roadmap looked like at different points in time over a year what are we giving to customers. How do we plan our customer projects around these different product releases.

The need was clear,I needed some kind of high-level product roadmap. But as a new leader to the team I was feeling the pressure to do exactly what was asked. You know I wasn’t the expert on this, right? These executives have been doing this a long time, they probably know more of the what. But something felt wrong. How am I going to get my team to commit to these timelines but we don’t even know what the work is, or how big it is? And then plan that out a full year in advance? My gut is telling me to fight it, my head is having a hard time rationalizing why.

Now at the time I didn’t know there was a whole bunch of product management techniques around this. Of how do you establish flexibility in a product roadmap. How do you keep a roadmap high-level, investment themes? How do you convey plans without commitment? Right, like I was just trying to figure stuff out of the time. But, even if I had all the tools at that time, I knew everything about product management, somehow, magically put in my head - would I have fought back against executives in that scenario? Or would I have caved to what upper management was asking, being the new leader, being someone with inexperience. I feel like now, with the experience I have, I would feel comfortable in punching upwards and it wouldn’t feel as awkward. But when you become a new leader in a team you don’t feel like you just really have that credibility have that weight so it can be tough. It can be tough to do that punching.

Slide 24

What did I learn?

Now I learned from these scenarios. I learned that what I needed to do as a leader was to say no. I knew I needed to fight for my team and say “hey this is not happening”.

Every time I tried to make everybody happy at the expense of my team it did not pay off. And ultimately it was eating away at my own credibility as a leader.

So I needed to make sure that I had the tools in place to be able to do my best job as leader. And I knew I had to try to fight harder.

But I still struggle with “no”. I mean, it’s built into me to support people and help them. I really hate not doing that. I started to learn that others are experiencing the same challenges, that they are also constrained. Often why they’re asking for something, right? And they understand the same lack of resources, cuz they’re having the same issue.

But I also know that sometimes saying “no” doesn’t work. I’ve gone in and, you know, I’ve pushed back and said “We can’t do this” and I’ve been told “Do it anyway”. Yeah, I’ve learned that one, had to do that. But I felt like when I look back on those scenarios that at least I could say I was fighting for my team I did everything I could to make sure my team was going to have the best scenario for them.

Slide 25

Avoiding burnout.

The last topic I want to take on is very important to me. And it’s about Mental Health. There must be a billion things written about mental health, and burnout, and trying to do self-care and balancing work life. I don’t want to rehash all that, but I think that folks like us who are doing a transition between being a member of a team into then leading a team, we face this unusually high percentage of having this burnout, because it’s a lot to take on.

And, like I said earlier, it’s hard to pass that stuff off that you’ve been doing previously. There’s all these built-up expectations of what you do today, and now there’s a bunch of expectations of what you’re going to do next.

Slide 26

Is management right for me?

I spoke earlier about when I was managing the R&D team, and how I decided to do both jobs. And I eventually burned myself out in under a year. I was not doing well. I certainly felt like I’ve been doing two jobs for that year. At one point I had so little left in tank I just started looking, around started trying to find something that was not management. So I was pinning it completely on all that strategic management work. I felt I must not be the right fit,I’m not the same as these others that are up here doing management. I needed to change. I needed to find something that was more like an independent contributor, something that didn’t have strategy. More task-based.

I knew I’d seen in my own team a lot of people go back and forth between being the manager and going back to Independent, that this is a common thing, so I figured wasn’t going to be a big issue. And at the very least I could find myself more comfortable. Maybe that would make me feel a little bit better.

So, took a new job and about 3 months into that job I started trying to lead groups, join tiger teams, suggest process changes. I could not help myself. I was probably doing more strategy work in that position then I’d been doing at my previous job. And somehow I was feeling better. How’s that working out?

The hint is, it was the two jobs. See, when I went to this new job I didn’t have any baggage of what I should have been already doing. There was nothing I had to get rid of in order to take on that extra level. I was the one that was a problem, yes, but it wasn’t that I wasn’t a match for leadership, I wasn’t a match for management. The problem I had was I didn’t transition. I didn’t do all the things I knew I had to do like delegating, all that, to transition from being a member of the team to then leading that team.

Slide 27

Hello March 601st

Now more recently March 2020 landed for me. A lot of people over the last year have had really challenging times and it’s been a very hard year for a lot of folks. I thought I had it pretty good. I thought I balanced things pretty well with my work as a manager and also as an independent contributor. I already worked remote before any of this pandemic happened, but when it hit felt like stuff was just piling up and it’s like. I just hit a limit. I didn’t understand what was happening.

Because I was already a remote worker, nothing had changed. Essentially my work balance of items were not changing, I hadn’t taken on anything big and knew. I wasn’t trying to do too much independent contributor work. I was trying to balance everything there.

But it turns out if you spend a year with a whole bunch of unknown things in your personal life and a whole bunch of unforeseen changes that you weren’t preparing for. It starts to add up.

So I started to recognize some of the feelings I was having were very similar to the last time I had burnout. It didn’t seem to be this management thing this time around. I knew what to expect. I’d made sure to balance my work roles, and I made sure to try to delegate as much as possible, and balance between work and home. Or so I thought. I seemed to do my best to keep everything under control and avoid the two jobs thing.

What didn’t occur to me was I was focusing completely on balancing work and making sure that those didn’t overload and then keeping a certain amount for life. But I didn’t take into account that my life part of the equation had grown, and needed much more than before.

Slide 28

Dealing with loss

Dealing with the pandemic was one example of having to balance personal life with work life. Over the last few years, my family also had another thing weighing over us on the personal life side of the ledger: my mother-in-law, Pat, had been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. For 2 years, much of it during the pandemic, our family day-to-day life was very different. We made everything we could out of every day.

Over this past summer, things took a turn. My family needed me, and not just during the off hours. The balance was fully weighed down on one side. Dealing with loss as a family affects your work to a huge extent.

Here I was, leading a team of great people, with major projects underway, and I couldn’t be there for them. I tried to have a few hours here and there, trying to keep things moving. I held some office hours regularly so that people could get in touch with me if something urgent came up, but for the majority of every day my team was on their own.

This was one of the things I learned from the pandemic: that need for balance. I knew that if I kept trying to do all of my work and also try to support my family in the way they needed, there wouldn’t be much of me left functioning in the end. As it was, it was incredibly tough to keep a straight face during some calls. It was hard to prioritize things like quarterly reporting. It was tough to see important projects moving along without me.

After mum passed away, I took some time to roll myself slowly back into a work schedule. And then I realized something: I had a conference presentation. I was presenting this very talk, minus this topic, two weeks after her passing. I wasn’t sure I could do it. I wasn’t sure it would be smart to do it. So I made a decision: I was not ready to talk about things. So I provided a pre-recorded version of the talk I had used for a different conference, made sure I was available as a backup, and did some text-based support for questions and social media. I made it through and out the other side, giving me time before the next major event to build up the mental space for presentations. I think it’s important that we look to ourselves in these situations and understand what we can handle. Maybe somebody else would have been able to do that talk, but for me, at that time, it was just not going to happen. And I needed to know that and take care of myself first. Now, today, I’m talking to you about this really important topic. And none of this would have been possible without having an understanding management team that supported me and allowed me to do what was right for myself and my family. I realized during this that one of the things that was most required in leadership was investing in your people and managing burnout. As a leader, you need to focus on managing yourself, but you also need to watch for those on your team. What can you do to make room for your team members to be healthy? How can you make sure they have what they need? What questions do you need to ask? And when things happen, how do you react and support them?

Loss is a heavy burden to carry, and sometimes you need help to make it through.

Slide 29

What did I learn?

In the end, what these stories taught me, was that I needed to learn about how to balance better. There’s a thread by someone on Twitter: @JenPlusPlus, who went really well into this. And talked about burnout and how often we are the ones who are put on to fix this. We’re told things like “Go have a vacation, you’ll feel better”. But it’s not fixing the underlying issue, right? It’s just a temporary fix. You wind up coming back to the exact same systemic issue that is there. And unless you resolve that systemic issue you don’t solve for the long game. And so, balancing is a way of trying to be part of that solution for the systemic issue. And what I learned was it’s not just about work-life balance, it’s about balancing what can you handle from a mental health load, and look at all the aspects. Sometimes your life might need more of the balance than others.

The biggest thing to help me in learning this was that I started recognizing my Burnout symptoms. And now, monitoring your own mental health is not something that is easy to do. If you can get professional help for it that is awesome! But what I did know is that a short vacation was not going to do this. It’s not always going to solve the main problem, and you can’t always solve it by just balancing work responsibilities.

So sometimes, for me, it’s been about saying no to things, right? Reducing the number of things that are on my plate so that I can have fewer things that I’m having to focus on. And sometimes it’s about having a recharge outlet, like a hobby, right? For me, if I do 30 minutes of playing some video games on the Xbox, you know, I can feel myself starting to recharge, rebuilding my capacity. Sometimes it’s about shifting between different task types. Whether it’s procedural or strategic, right? Like if you’re doing too much of one, maybe take a break from that and give your brain a little bit of a rest. It’s all about not overloading yourself. It’s kind of a marathon, it’s a very long game we’re running in and we have to ration ourselves. We have to be doing the things that are going to keep us going over that time.

Slide 30

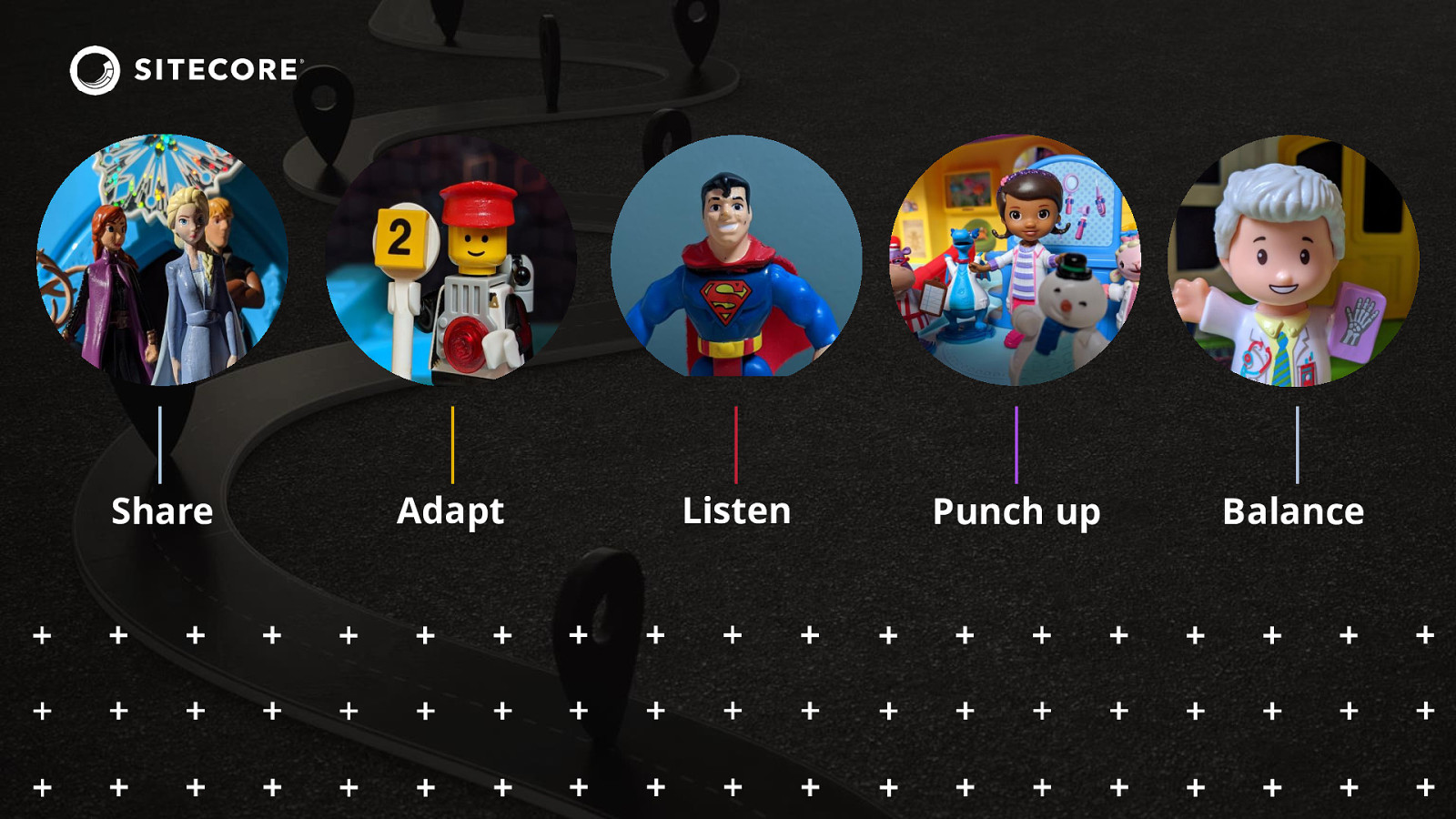

Now across this session I mentioned we’d look at those specific challenges and we looked at five topics. And you can use these and the stories in them to take those lessons as building blocks. Things that you can then do to start addressing other challenges that you see match in management.

Slide 31

Now, the first thing we looked at was how do you share your load? How do you learn to delegate more of your tasks and take on a more strategic role on the team.

The second one we looked at was focusing on adapting. Right? Using everything and all the tools available to you, and accepting that sometimes you don’t have all of the answers.

Next, and this is probably one of the most important ones, was listening. How do we make sure that we’re not being the hero, we’re not being the expert. Our leadership success is going to be about how well I can listen to others and make them the focus.

Also we need to learn how to say no, punch up for our team. How do we fight for our team and help them be able to do what they need to do.

And the final section was how do we balance? How do we monitor our mental health and make sure we’re balancing everything in our lives so that we can be here and ready that long game.

Now there’s a lot of stories we went through. Hopefully some of those experiences of mine are going to resonate with something you’re experiencing. There’s a bunch we didn’t go into today but if use these basic building blocks, I think you’re going to be able to find you can face a lot of things new challenges.

Slide 32

I know you got this! But, I’d like you to connect. Really, I want to hear about what are you going through? What challenges are you seeing?

For me this is a continuous learning path and hopefully we’ll see each other out there together.

Thanks! I’ll see you in the Discord channel if you have any questions or want to talk!